The History of the Cable Car

Material ropeways made of hemp ropes were already used in antiquity to overcome gorges and rivers. There are also descriptions of ropeway-like installations from the Middle Ages, which were mainly constructed to siege fortifications and for other military purposes. Passenger cable cars, however, had never been attempted or officially approved before and posed certain difficulties.

Nonetheless, the innkeeper Josef Staffler was determined to find a quick and simple way for guests to reach his inn on Kohlern. In 1908, after many setbacks and delays, Staffler’s cable car was officially approved. Hence, Staffler’s entrepreneurship paved the way for new ways of mountain transportation.

The founding years

In 1859, the dawn of the railway age brought profound changes to the local economy. Overnight, the time-space relationship had changed; with the railway, distances shrank, travel times were reduced many times over and completely new perspectives opened up for tourism and the export of local goods.

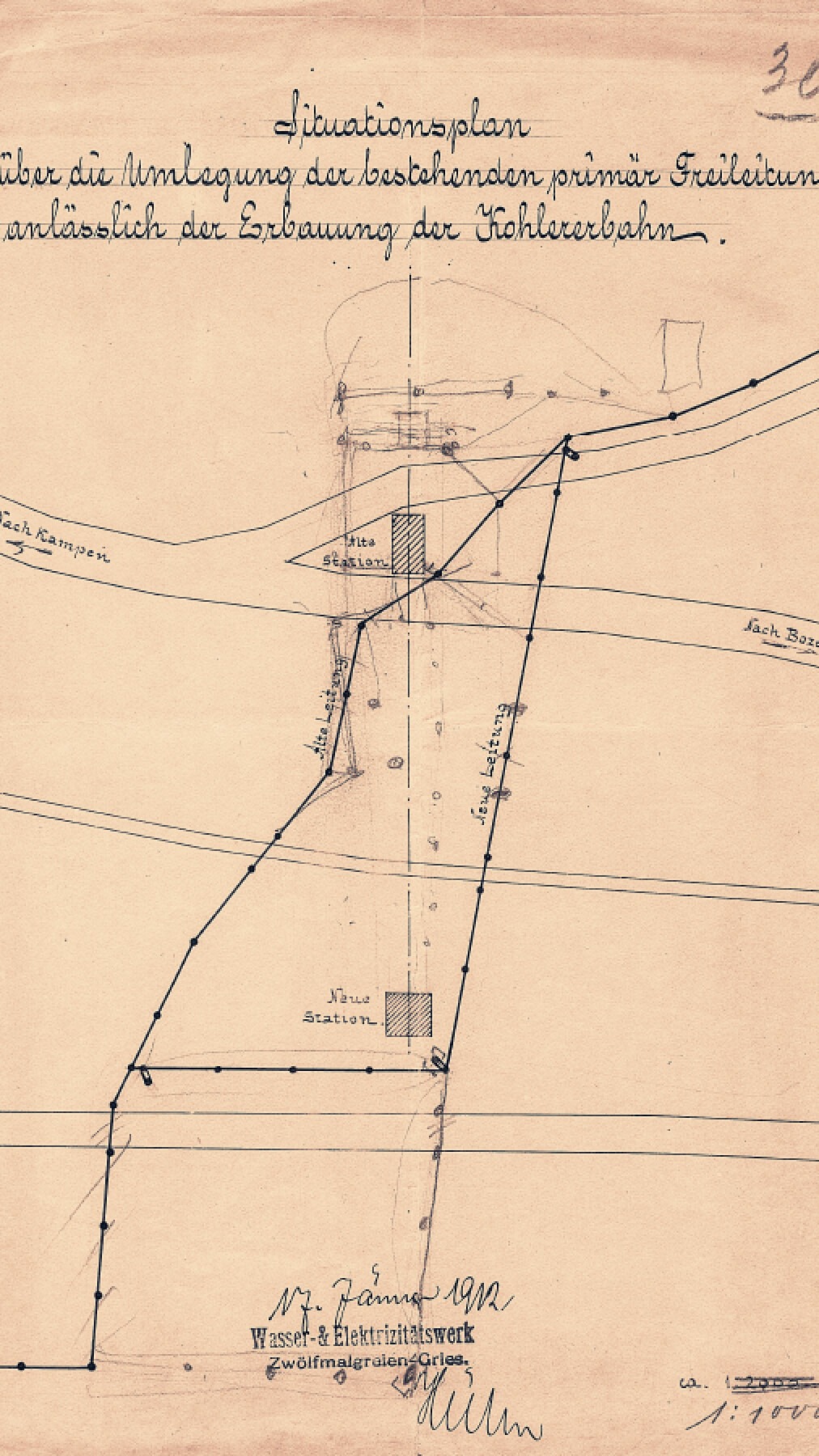

In 1895, Julius Perathoner was elected mayor of Bolzano. He was to hold the office for 27 years before he was deposed by the fascists. His programme focused on modernisation and included the construction of schools, roads, promenades and bridges, as well as the electrification of street lighting. These changes were made possible by the construction of a large hydroelectric power station on the Töll above Merano in 1898.

Bolzano had almost 12,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the 20th century and tourism was flourishing. Gries and Zwölfmalgreien were independent communities at that time. Gries in particular was popular with wealthy international guests as a health resort during the winter months. Queen Therese of Bavaria and Duke Franz of Austria Este Modena appreciated the sunny, and pleasantly wind-protected location just as much as Russian aristocrats.

Then in 1898, the 15-kilometre-long steam railway from Bolzano to Caldaro went into operation, paving the way for the first large mountain railway in the Bolzano area: the funicular from the fraction of St. Anton to the Mendola.

Transporting goods

Simple ropeways made of hemp ropes were already built in antiquity to overcome gorges and rivers. There are also descriptions of ropeway-like installations from the Middle Ages, which were mainly used for the siege of fortifications and for military purposes. The development of cableways in today’s sense dates back to the invention of the wire rope at the beginning of the 19th century. Initially, material ropeways were built mainly in the USA for mines.

From 1874, Adolf Bleichert from Leipzig also mass-produced wire ropeways in Europe. Annual production peaked in 1900 with 345 cableways delivered, one year before Adolf Bleichert died and his sons Max and Paul took over the company. They were soon supplying ropeways worldwide and made headlines when they built a 34-kilometre-long material ropeway in Argentina in 1905, which covered a height difference of 3,528 metres. Although this cableway was only designed for material, there was also a limited amount of passenger transport. However, only employees of the cable car were transported, and this was the sole responsibility of the cable car operator, without legal authorisation or government regulations.

The pioneer

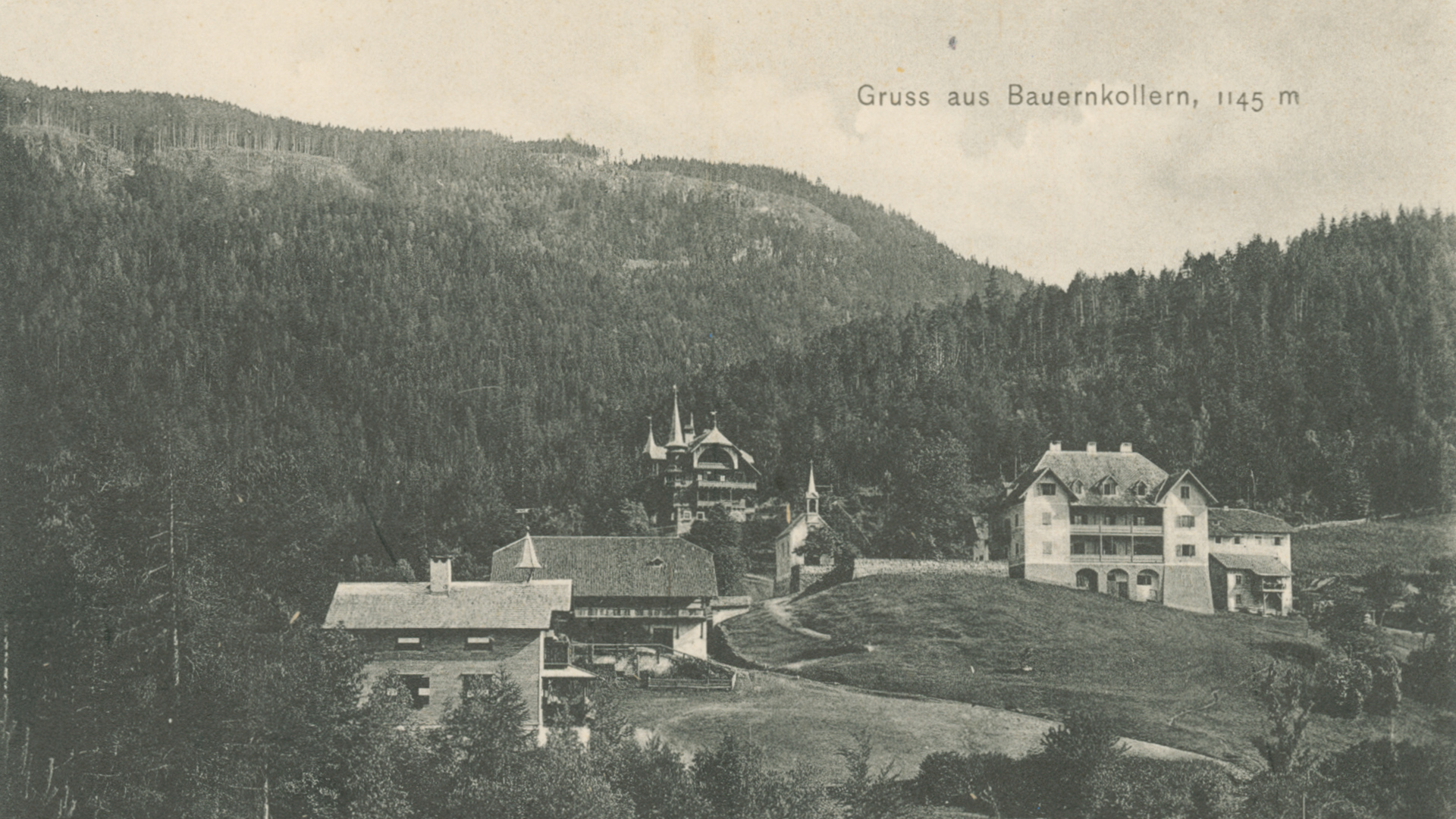

The Bolzano innkeeper Josef Staffler (*17 March 1846) bought the Uhlenhof in Bauernkohlern in 1899. It included woods, a chapel and a manor house in a wonderful panoramic location, which Staffler had converted into a high-altitude inn. But how were his guests to manage the 900 metres in altitude from Bolzano? The choice was between a two-hour walk or strenuous transport on a bumpy kart track.

So Staffler had his first ideas for an electric cable car, but everything was too expensive. So he turned to the plan of an “electrically operated wire rope lift”; a project that seemed affordable and technically possible. But “in view of the non-existence of a track on the ground”, the railway was not a railway in the technical sense – at least that was the explanation from Vienna – and thus not part of the jurisdiction of the Imperial and Royal Railway Ministry.

Nevertheless, after the commissioning of his project in June 1905, Staffler received permission from the district administration of Bolzano to build a wire rope lift for transporting materials, which was collaudited a year later. The wire rope lift was partially run so low that it was easy to jump in and out of the transport box near the bottom station. After initial attempts to stop the lift, Staffler again attempted to obtain official approval for passenger transport and was thus able – after equipping his cable car with new safety precautions for passengers – to put the world’s first mountain cable car approved for passenger transport into operation on 29 June 1908.

Calculating the weight

The gondolas of the first Kohler Railway deserve a special mention. Their design, which almost resembles a coach box, is initially characteristic of passenger transport by air. The transition to metal cabins was marked, in the same summer, by the Wetterhorn lift near Grindelwald in Switzerland. According to the recollection of Josef Staffler’s grandchildren, the first Kohler lift had actually been completed in 1907, but the authorities at the time had not approved the gondolas for safety reasons. The Simmeringer Waggonfabrik in Vienna then built new gondolas, but these did not comply either. The Viennese gondolas were so massive that each of them weighed 400 to 500 kilos and, in addition, their lower edge on the valley side got caught on the cross beams of the cableway stands, which had been taken over from the material railway.

Now Staffler contacted the master wainwright Thomas Peer from Terlan. During his years of apprenticeship and travel, Peer had also learned how to build carriages, and now he made two light gondolas in the manner of carriages, with a roof consisting of only one sheet. Peer delivered his work in mid-June; the customs scales at the north end of the Eisack bridge showed 195 kg for each gondola. Fully loaded with bricks, they mastered a successful, if at first somewhat dramatic-looking test run.

(Excerpts taken from the brochure The world’s first mountain suspension railway Bolzano—Kohlern, published by the Heimatschutzverein Bolzano in 1983, Author: Norbert Mumelter)

The safety

The first Kohler railway remained in operation for two years. Curious people flocked from near and far to dare a ride. Over 100,000 people were transported accident-free during this time, and yet the operation had to be discontinued in October 1910 because the supervisory authorities had issued new regulations. They now demanded a cable car with pendulum operation, double carrying and hauling ropes as well as safety brakes on the gondolas. In contrast to material ropeways, the rope safety was to be fivefold.

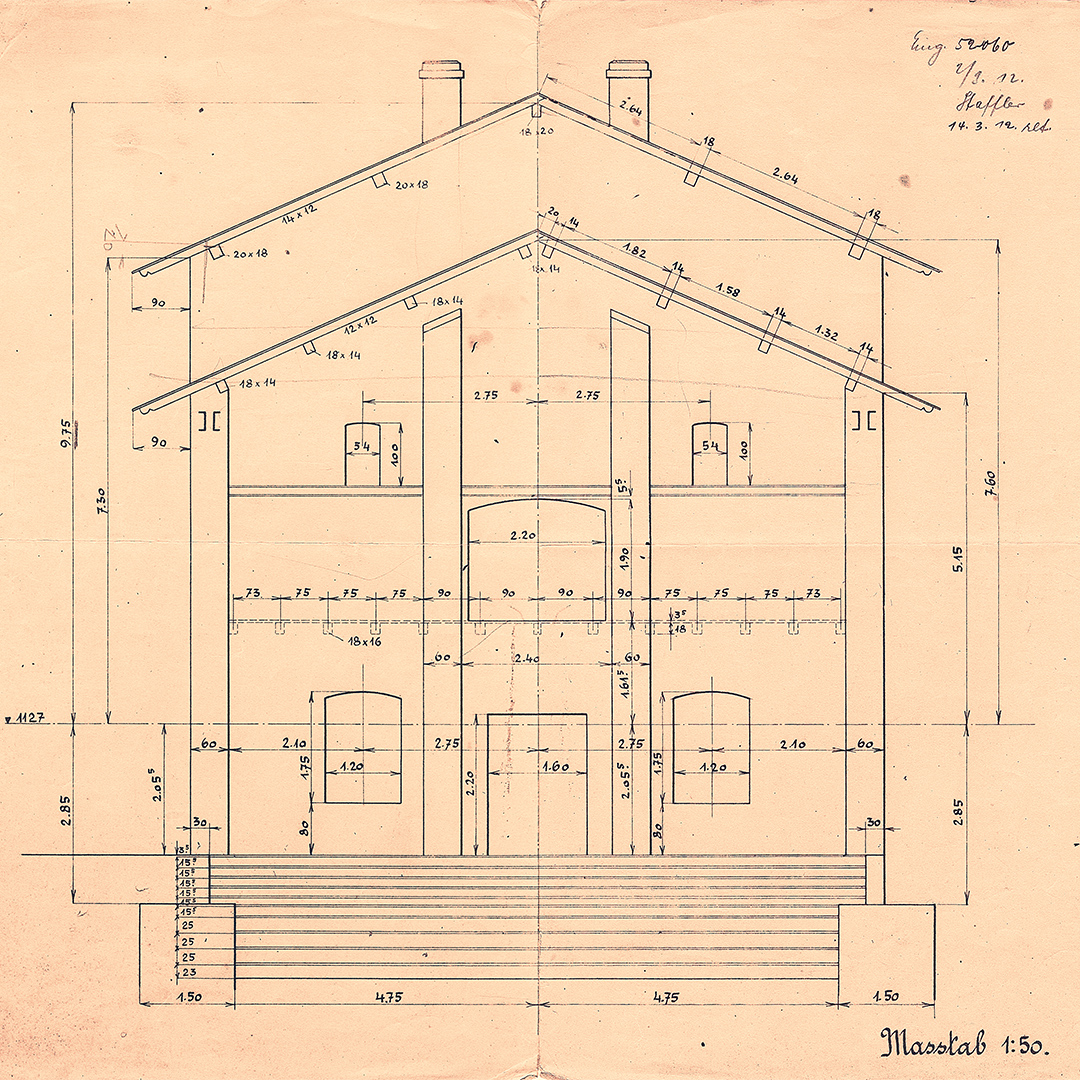

The Bleichert company agreed to comply with all safety precautions. The new valley station was now about 150 metres lower; the design was by the Munich architect August Fingerle (1854-1949). Staffler also decided to order much larger cabins to increase the hourly capacity of the cable car.

The Imperial and Royal Ministry of Railways in Vienna considered the new cable car to be the best solution. In the meantime, the Imperial and Royal Ministry of Railways in Vienna regarded the Kohler Railway as a kind of test installation for the preparation of the “Regulations for the Construction of Suspended Railways Serving Public Passenger Transport”. All the experience gained here was considered in the formulation of the new licensing regulations. For example, the ministry ordered no fewer than 96 catch tests and tension measurements.

At the time, only three other passenger cable railways were in operation worldwide besides the second Kohler Railway: the Wetterhorn lift in Grindelwald (1908) in Switzerland, the first Vigiljoch lift near Lana (1912) and the cable railway up the Sugar Loaf Mountain in Rio de Janeiro (1912).

Surviving two wars

Barely two years after its opening, the second Kohler Railway faced increasing problems, because when Italy declared war on Austria in 1915, the railway’s employees, including the then irreplaceable machinist, were also forced to enlist. On 2 June 1915, the city council of Bolzano ordered the closure of the railway until a new manager was hired. However, Staffler still allowed the railway to operate and received a first warning in 1917.

When an accident with personal injury occurred on 9 July 1918, the governor of Tyrol and Vorarlberg intervened and again ordered the closure of the railway. Staffler asked for the resumption of freight traffic and pointed out that from 1917 to June 1918 the railway had transported no less than 3,000 cubic metres of wood for the city hospital, the municipality and the soldiers’ hospitals from Kohlern to Bolzano. There were also still several thousand cubic metres of wood ready for transport. On 20 August 1918, the operation of unaccompanied freight wagons was finally authorised.

After the First World War, the railway was also allowed to transport passengers again and Kohlern was mainly visited by local guests and summer visitors. However, during the fifth major Allied air raid on Bolzano on 25 December 1943, the valley station was severely damaged. The Second World War thus put an end to cable car transport for the time being, until the third Kohlern cable car began operating in 1965.

»When the Second World War ended in May 1945, steel helmets were still lying on the Titschen — as in a frontline area — for years.«

Texts are based on the research of Wittfrida Mitterer and Norbert Mumelter. Additional information can be found at the Tecneum, Kuratorium für Technische Kulturgüter.

Image Credits: Amt für Seilbahnen Bozen | Ufficio Funivie Bolzano