The Ropeway Pioneers

The cable car as a means of transport has left its mark on the mountain world over the years. It brought both comfort and challenges for planners, engineers, businessmen, and passengers alike, due to the often impassable terrain that had to be made accessible. But it was precisely these challenges that prompted ingenious solutions and masterpieces of technology that still change our everyday lives.

Many people have contributed to making the cable car what it is today: a fast, safe, comfortable means of transport. Not all of these pioneers have received the recognition and attention they deserve. A few pioneers are therefore listed below, also representative of all those not mentioned, but have played a big part in the history of the cable car.

Artur Doppelmayr

Lift systems with movable or floating’ glacier supports, the break-rod switch, which simplified the shutdown of the line circuit for safety purposes, seat heaters for chairlifts or panoramic glazed weather protection bonnets known as “bubbles” – milestones in ropeway technology that go back to the entrepreneur, technician and engineer Artur Doppelmayr.

The Vorarlberg ropeway pioneer was born in Dornbirn in 1922 as the son of Melitta and Emil Doppelmayr. He was drafted at the age of 19 and did not return from captivity until November 1945. He graduated from the Technical University of Graz in 1954 with a degree in industrial engineering and mechanical engineering and joined the company founded by his grandfather one year later. His grandfather had set up his own forge at the end of the 19th century and specialised in the production of spindle and hydraulic presses, turbines and woodworking machines.

When his father Emil took over the management in 1928, he put his trust in new ideas and pushed ahead with the construction of lifts. In 1937, together with Sepp Bildstein, he built Austria’s first surface lift in Zürs. Artur also focuses on innovation and pushes the development of ropeway-operated systems and the expansion of the export business. He succeeds in making the family business the world market leader in ropeway construction in just a few years. Today, numerous ropeways of the Doppelmayr/Garaventa Group, led by son Michael (as of 2021), can be found all over the world.

Gabriel and Ernst Leitner

In an obituary, the company founder Gabriel Leitner, who was born in 1857, was praised as a ‘man full of energy, enduring creative joy, [and] a pioneer of work’ (Meraner Zeitung, 2 January 1926). The described creative spirit can also be seen in his numerous mechanical inventions, technical achievements and constructions. Gabriel began building agricultural machines, mills and water turbines at an early age, until he finally founded his own company in 1888.

His curiosity was not limited to the agricultural sector. He seems to have been driven by a general desire to optimise production processes and everyday life. In Sterzing he replaces the steam operation of a dairy with an electric motor and thus manages to save coal. In Telfes he builds a cable car for the daily transport of milk, including an electric power station, which also supplies the surrounding villages with electricity, and in 1908 he is involved in the construction of the Kohler cable car, the first passenger cable car in the world.

After studying mechanical engineering, his son Ernst joins his father’s company and continues to drive ropeway production forward. In 1947, Erich Kostner commissioned Karl Hölzl to build a single chairlift on Col Alto in Corvara. This is soon followed by projects throughout Italy, Austria and Germany. Through Ernst, but also through his sons Kurt and Ernst jr., the Dolomites are opened up by lifts and cable cars, and they also break new ground in the discovery of the cable car as an urban transport system. In many South American metropolises today, the urban cable car functions efficiently as a solution to traffic and transport problems.

Luis Zuegg

The inventor, businessman and father of modern cable car technology, Luis Zuegg, was born in Lana in 1876. Already as a young engineer he built an electricity plant in the Gaulschlucht in Lana and the Lana-Meran tramway. He also founded a cardboard factory in Lana in 1908, where waste wood is processed into cardboard. The wood is transported down to the valley from the surrounding, impassable terrain by material ropeways. When the Lana-Vigiljoch aerial cableway cannot be completed due to safety deficiencies and the death of the project engineer Emil Strub, Zuegg steps in and, thanks to his expertise, successfully completes the project in 1912.

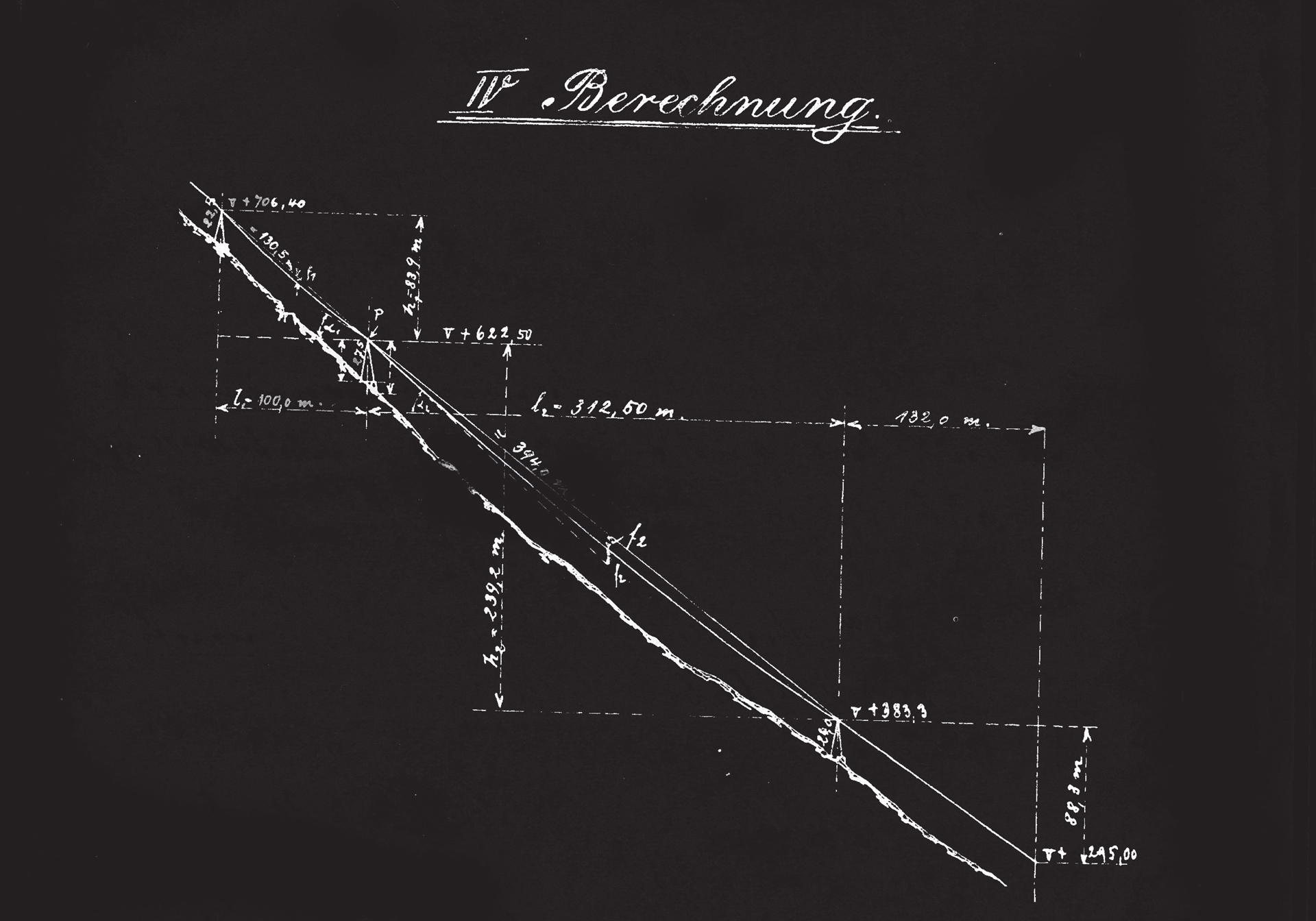

During the First World War, Zuegg made a name for himself as a Landsturm engineer. He builds a cableway from Sesto to the Monte Elmo, and is able to complete the cableway despite the fact that the suspension cable is too short, thanks to a tighter cable tension. Zuegg thus proves what he had long suspected: tighter tension extends the service life of the ropes, enables greater spans and increases the speed of travel.

Other innovations in the next few years are the automatic cabin brake, in which the gondola is clamped to the track rope when the tension is released, and the telephone in the gondolas. Here, the earthed suspension cable and the insulated haul rope are used as conductors to transmit messages from the cabin to the mountain or valley station. Soon Luis Zuegg cooperates with the company of the Bleichert brothers and builds railways all over the world using the “Bleichert-Zuegg system”, which has since been patented.

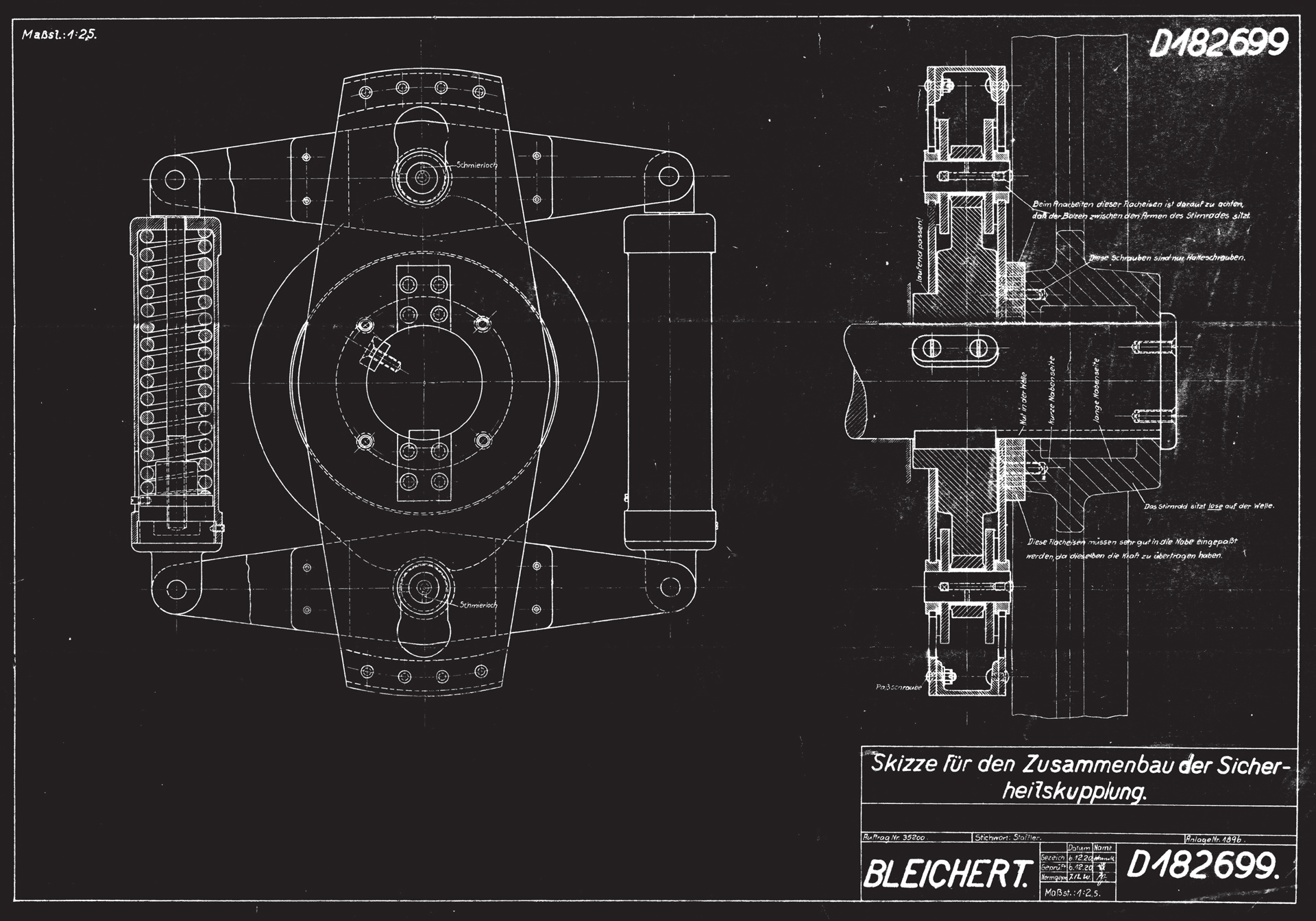

Max and Paul von Bleichert

Adolf Bleichert, the father of Max and Paul, successfully built material ropeways as early as 1874 together with his student friend Theodor Otto. In 1881 he founded the “Adolf Bleichert & Co.” company in Leipzig-Gohlis, a company specialising in cableways, which realised over a thousand cableway projects until his death in 1901. His sons continue to run the company successfully. Max drives the technical research and production, while Paul takes care of the entrepreneurial part, as well as the social policy of the company.

Between 1910 and 1913, they were involved in the construction of the second Kohler cableway, implementing the new safety regulations issued by the supervisory authority at the time. They then build material and passenger ropeways all over the world until they have to change their production during the First World War. Now they produce ammunition and field ropeways, which are not only used for supply purposes, but also to transport injured people from the battlefield.

In the following years, Paul has to retire from working life for health reasons, and the company is not unaffected by external factors: increased competition and the world economic crisis take their toll. Max is threatened with insolvency at the end of the 1920s and so the company can no longer be run as a family business. In the following years, the company underwent many changes and no longer exists as such – but Bleichert streets in Leipzig and Berlin are a reminder of the pioneering achievements of the Bleichert family.

Texts are based on the research of Wittfrida Mitterer and Norbert Mumelter. Additional information can be found at the Tecneum, Kuratorium für Technische Kulturgüter.

Image Credits: Amt für Seilbahnen Bozen | Ufficio Funivie Bolzano